Tuesday, January 17, 2006

TURKISH ART

CALLIGRAPHY / Decorative Turkish Arts

The first thing that comes to mind whenever calligraphy is mentioned is the decorative use of Arabic letters. This art emerged after a long period between the 6th and 10th centuries as Arabic letters evolved.

After turning to Islam and adopting the Arabic alphabet, the Turks failed to play any part in the art

of calligraphy for a long time. They first began to show an interest in it after moving to Anatolia, and the Ottoman period was one of the times during which it flourished most. Yakut-ı Mustasımi was particularly influential in Anatolia from the beginning of the 13th century to the middle of the 15th. Şeyh Hamdullah (1429-1520) made a number of changes to the rules introduced by Yakut-ı Mustasımi, thus giving Arabic letters are warmer, softer appearance. Şeyh Hamdullah is regarded as the father of Turkish calligraphy, and his style and influence predominated until the 17th century. It was Hafız Osman (1642-1698) who produced the art's most aesthetically mature period. All the great calligraphers who came after basically followed in Hafız Osman's footsteps.

As well as the six main styles of calligraphy, the Turks also created a new style from the 'talik' form discovered by the Persians. The early examples of this 'talik' style were

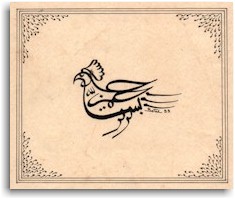

"Zoomorphic" calligraphy: the script means "

In the name of God" and forms a bird; its neckband reads "O merciful, O Compassionate".

heavily influenced by Persia, but in the 18th century mehmed Esad Yesari (died 1798) and his son Yesari Mustafa İzzet (died 1849) gave it a whole new appearance. Turkish calligraphy continued to shine in the 19th and 20th centuries. With the adoption of the Latin alphabet in 1928, however, it ceased to be a popular art form, becoming merely a traditional art taught in a certain number of schools.

ILLUMINATION AND GILDING / Decorative Turkish Arts

Known as 'tezhip' in Turkish, this is an old decorative art. The word 'tezhip' means 'turning gold' or 'covering with gold leaf' in Arabic. Yet 'tezhip' can be done with paint as well as with gold leaf. It was mostly employed in handwritten books and on the edges of calligraphic texts.

The art of ilumination has been practiced as widely in the West as it has in the East. In the Middle Ages in particularly it was widely used to decorate Christian religious texts and prayer books. Gradually however, picture illustrations became more popular, and illumination became restricted to decorating the capital letters in main headings.

Among the Turks, the history of illumination goes back to the Uyghurs, and first began to be seen among the Uyghur people in the 9th century. The Selujks then brought it to Anatolia, and the art saw its culmination in Ottoman times. Mameluke artists in 15th century Egypt developed their own style, and great advances in the art of illumination were made at the same time in Persia and then in such cities as Herat, Hive, Bukhara and Samarkand which were ruled by the Timurs. The style that developed in Herat later had great influence on the Persian art of illimunation. As a result of growing ties with Persia in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ottomans adopted many of the features of the Herat School in their own work, and created new syntheses. In the 18th century, the Ottoman art of illumination began to fade, with crude decoration replacing the classical motifs. In the 19th century, the Western influence that could be seen in almost all areas of art also began to make its presence felt in the art of illumination. For example, flower motifs that used to be employed singly on vases during the classical period now began to appear in groups in pots.

The main ingredient in illumination is gold or paint. Gold is used in a thin leaf prepared by beating it to an extreme fineness. The gold leaf is powdered in water and mixed with gelatine, and then brought to the desired thickness. Earth paints tended to be preferred in terms of paint, although synthetic paints were employed later. The illuminator, known as the 'müzehhip,' first uses a needle to impress the designs he has drawn onto paper attached to a hard boxwood or zinc base. He then places the perforated paper onto the material he intends to decorate, and fills the holes with a sticky, black powder. When the paper is removed, the design is left behind. The motif is then rounded out and filled with the gold leaf or paint.

MINIATURE WORK / Decorative Turkish Arts

This is the name given to the art of producing very finely detailed, small paintings. In Europe in the Middle Ages, handwritten manuscripts would be decorated by painting capital letters red. Lead oxide, known as 'minium' in Latin and which gave a particularly pleasant colour, was used for this purpose. That is where the word 'miniature' derives from. In Turkey, the art of miniature painting used to be called 'nakış' or 'tasvir,' wit

h the former being more commonly employed. The artist was known as a 'nakkaş' or 'musavvir.' Miniature work was generally applied to paper, ivory and similar materials.

h the former being more commonly employed. The artist was known as a 'nakkaş' or 'musavvir.' Miniature work was generally applied to paper, ivory and similar materials.The miniature is an art style with a long history in both the Eastern and Western worlds. There are those, however, who maintain that it was originally an Eastern art, from where it made its way to the West. Eastern and Western miniature art is very similar, although differences can be observed in colour, form and subject matter. Scale was kept small since the art was used to decorate books. That is a common characteristic. Eastern and Turkish miniatures also possess a number of other features. The outside of the miniature is usually decorated with a form of embellishment known as 'tezhip.' A paint similar to water colour was used for miniatures, although rather more gum arabic was used during the mixing process. Very thin brushes made from cat fur and known as 'fur brushes' were used to draw the lines and fill in the fine detail. Other brushes were employed for the painting itself. White lead with gum Arabic added was applied to the surface of the paper to be painted. A thin coat of gold powder would also be applied to the surface to make the various colours transparent.

The oldest known miniatures were done on papyrus in Egypt in the 2nd century BC. Handwritten manuscripts decorated with miniatures can then be observed in the Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Syriac periods. With the spread of Christianity, miniatures began to be used to ornament the Bible in particular. The development of the art came towards the end of the 8th century. In the 12th century, miniatures ceased to be directly linked in form to the text they were decorating, and also ceased to be exclusively religious in tone, with secular examples appearing. Beautiful and splendid miniatures continued to be created in Europe until the development of the printing press. After that time, they were more usually used in the form of portraits on the backs of medallions. After the 17th century, the application of miniatures to ivory began to spread. Later still, as interest in the art of the miniature began to fall, it continued as a traditional art

form among a small number of artists.

form among a small number of artists.Great importance was attached to the miniature during the Seljuk period. Seljuk miniature was considerably influenced by Persia, on account of their close relations with that country. They also produced Abdüddevle, who painted a portrait of Mevlana, and other famous miniaturists. In the Ottoman Empire, the Seljuk and Persian influence continued up until the 18th century. During the time of Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror, a miniaturist by the name of Sinan Bey made a portrait of the sultan, and also trained another artist called Baba Nakkaş during the reign of Bayezid II. In the 16th century, the artists Nigari, known as Reis Haydar, Nakşi and Şah Kulu won considerable renown. During that same time, Aka Mirek of Horasan, a student of Bihzad, was called to Istanbul and made 'başnakkaş' or chief artist. Mustafa Çelebi, Selimiyeli Reşid, Süleyman Çelebi and Levni were the best known miniaturists of the 18tth century. Of these, levn' constituted a turning point in Turkish miniature painting. Levn' moved beyond the traditional conception of the art and developed his own unique style. Under the influence of the renewal movements in the 19th century, Western art also began to affect the art of miniature painting. The miniature slowly began to give way to contemporary art as we understand the concept today. However, it still survives as a traditional art in Turkey, in the same was as it does in the West.

MARBLING / Decorative Turkish Arts

The art of marbling on paper, or 'ebru' in Turkish, is a traditional decorative form employing special methods. The word 'ebru' comes from the Persian word 'ebr,' meaning

'cloud.' The word 'ebri' then evolved from this, assuming the meaning 'like a cloud' or 'cloudy,' and was assimilated into Turkish in the form 'ebru.' Marbling does actually give the impression of clouds. Another possible derivation of the word 'ebru' is

'cloud.' The word 'ebri' then evolved from this, assuming the meaning 'like a cloud' or 'cloudy,' and was assimilated into Turkish in the form 'ebru.' Marbling does actually give the impression of clouds. Another possible derivation of the word 'ebru' is from the Persian 'âb-rûy,' meaning 'face water.'

from the Persian 'âb-rûy,' meaning 'face water.'Although it is not known when and in which country the art of marbling was born, there is no doubt that it is a decorative art peculiar to Eastern countries. A number of Persian sources report that it first emerged in India. It was carried from India to Persia, and from there to the Ottomans. According to other sources, the art of marbling was born in the city of Bukhara in Turkistan, finding its way to the Ottomans by way of Persia. In the West, 'ebru' is known as 'Turkish paper.'

Sunday, January 15, 2006

WONDERS OF TURKIYE

Ephesus Artemis Temple

This famous temple is one of the seven wonders of the world, and is also known as Artemission. It was first built in lonian style during 560-550 B.C. by the Lydian King Kroisos. After being burnt down in 356 B.C. by a lunatic, it was rebuilt on the same foundations, but its height was extended by 3 m. This temple, which is also famous for its  marble statues, is 55.10 x 115 in dimensions and was the largest of all temple, which were discorered during digs by J.T. Wood in 1869-1874, and David G. Hogart in 1904-1905 in the name of the British Museum, were taken to England.

marble statues, is 55.10 x 115 in dimensions and was the largest of all temple, which were discorered during digs by J.T. Wood in 1869-1874, and David G. Hogart in 1904-1905 in the name of the British Museum, were taken to England.

It is the most important remains of the Ephesus antique city in the İzmir Selçuk province. Built during the Roman Period in 115-117, it survived a fire in the year 260. It is famous for its striking architecture of its two-story facade. The three rows of recesses in the inner walls of the library were used to store rolls of script.

The Rumeli Fortress

It is situated on the Tracean side of th e Istanbul Bosphorous.

e Istanbul Bosphorous.

It was built by Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror in 1452 to prevent aid from north reaching Byzantine. It took 4 months to build with 1000 masons and 2000 workers. The three towers were built by Çandarlı Halil Pasha, Saruca Pasha and Zaganos Pasha and are named after them.

The fortress has 5 gates and lies over an area of 30.000 m².

Istanbul City Walls

The first city walls of Istanbul were built during 413-477 by the Byzantine Emperor thedosius II. they extend 6-7 km. starting from the Marble Tower on the Marmara shore up to the Golden Horn. The Yedikule Walls was built by Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror in the years 1457-1458. These walls contain 16 gates. the walls have a three stage defence consisting of the inner walls, outer walls and a trench. The inner walls are 3-4m thick and 13m high. The outer walls 15m away, are 2m. thick and 10m. high. In front of the outer walls, there is a trench. The Istanbul city walls are being restored within the franework of the UNESCO protection program.

Dolmabahce Palace

Until the 17 th century the area where Dolmabahçe Palace stands toda y was a small bay on the Bosphorus, claimed by some to be where the Argonauts anchored during their quest for the Golden Fleece, and where in 1453 Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror had his fleet hauled ashore and across teh hills to be refloated in the Golden Horn.

y was a small bay on the Bosphorus, claimed by some to be where the Argonauts anchored during their quest for the Golden Fleece, and where in 1453 Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror had his fleet hauled ashore and across teh hills to be refloated in the Golden Horn.

This natural harbour provided anchorage for the Ottoman fleet and for traditional naval ceremonies. From the 17 th century the bay was gradually filled in and became one of the imperial parks on the Bosphourus known as Dolmabahçe, literally meaning “filled garden”.

A series of imperial köşks (mansions) and kasırs (pavilions) were built here, eventually growing into a palace complex known as Beşiktaş Waterfront Palace.

Beşiktaş Waterfront palace was demolished in 1843 by Sultan Abdülmecid (1839-1861) on the grounds that it was made of wood and incovenient, and construction of Dolmabahçe Palace commenced in its place.

Construction of the new palace and its periphery walls was completed in 1856. Dolmabahçe Palace had a total area of over 110.000 square metres and consisted of sixteen separate sections apart from the palace proper. These included stables, a flour mill, pharmcy, kitchens, aviary, glass maufactury and foundry. Sultan Abdülhamid II (1876-1909) added a clock tower and the Veliahd Dairesi (apartments for the heir apparent), and the Hareket Köşks in the gardens behind.

The main palace was built by the leading Ottoman architects of the era, Karabet and Nikoğos Balyan, and consists of three parts: the Imperial Mabeyn (State Apartments), Muayede Salon (Ceremonial Hall) and the Imperial Harem, where the sultan and his family led their private lives. The Ceremonial Hall placed centrally between the other two sections is where the sultan received statesman and dignitaries on state occasions and religious festivals.

The main palace was built by the leading Ottoman architects of the era, Karabet and Nikoğos Balyan, and consists of three parts: the Imperial Mabeyn (State Apartments), Muayede Salon (Ceremonial Hall) and the Imperial Harem, where the sultan and his family led their private lives. The Ceremonial Hall placed centrally between the other two sections is where the sultan received statesman and dignitaries on state occasions and religious festivals.

The palace consists of two main storeys and a basement. The conspicuous western style of decoration tends to overshadow the decidedly Ottoman interpretation evident most of all in the interpretation evident most of all in the interior plan. This follows the traditional layout and relations between private rooms and central galleries of the Turkish house, implemented here on a large scale. The outer walls are made of stone, the interior walls are made of stone, the interior walls of brick, and the floors of wood. Modern technology in the form of electricity and a central heating system was introduced in 1910-12. The palace has a total floor area of 45.000 square metres, with 285 small rooms, 46 reception rooms and galleries, 6 hamams (Turkish baths) and 68 lavatories. The finely made parquet floors are laid with 4454 square metres of carpets, the earliest made at the palace carpet weaving mill and those of later date at the mill in Hereke.

The Mabeyn where the sultan conducted affairs of state is the most important section in terms of function and splendour. The entrance hall known as the Medhal Salon, the Crystal Staircase, and the Süfera Salon where foreign ambassadors were entertained prior to audience with the sultan in the Red Room are all decorated and furnished in a style reflecting the historical magnificence of the empire. The Zülvecheyn Salon on the upper floor serves as an entrance hall leading to the apartments reserved for the sultan in the Mabeyn. These apartments include a magnificent hamam faced with Egyptian marble, a study and drawing rooms.

The Ceremonial Hall situated between the Harem and the Mabeyn is the highest and most imposing section of Dolmabahçe Palace. With an area of over 2000 square metres, 56 columns, a dome 36 metres high at the apex, and a 4.5 ton English chandelier, this room stands out as the focal point of the palace. In cold weather this vast room was heated by hot air blown out at the bases of the columns from a heating system in the basement. On ceremonial occasions the gold throne would be carried here from Topkapı Palace, and seated here the sultan would exchange congratulations on religious festivals with hundreds of staktesmen and other official guests. On such traditional occasions foreign ambassadors and guests would sit in one of the upper galleries, another being reserved for the palace orchestra.

The traditional Turkish palace was a complex of buildings with diverse functions rather than a single large building with an impressive façade. In this respect Dolmabahçe Palace is a departure from traditional concepts in imitation of western ideas. Inside, however, the Harem was as strictly isolated from the restof the palace as in earlier centuries, despite being under the same roof.

The self-contained Harem occupies two thirds of the palace, corridors linking it to the Mabeyn and the Ceremonial Hall. Access to the Harem was by iron and wooden doors, through which only the sultan could pass freely. Here are a series of salons and galleries whose windows look out onto the Bosphorus, and leading off them the suites of rooms belonging to the sultan's wives, the high ranking female officials of the Harem, and the sons, brothers, daughters and sisters of the sultan. Other principal sections are the suite of the Valide Sultan (sultan’s mother), the so-called Blue and Pink salons, the bedrooms of sultans Abdülmecid, Abdülaziz and Mehmed V. Reşad, the section housing the lower ranking palace women known as the Cariyeler Dairesi, the rooms of the sultan’s wives (kadınefendi), and the study and bedroom used by Atatürk. All the main rooms are furnished with valuable carpets, ornaments, paintings, chandeliers and calligraphic panels.

Restoration of Dolmabahçe Palace has now been completed and every section is open to the public. Two galleries are devoted to an exhibition of precious items of various kinds, and fine examples of Yıldız porcelain from the National Palaces collection are displayed at the İç Hazine (Privy Purse) building. Paintings from the National Palaces collection can be seen in the Art Gallery, where they are displayed in rotation in the form of long-term exhibitions. On the lower floor beneath this gallery is a corridor containing a permanent exhibition of photographs showing the bird designs which feature in the palace’s architecture and its furnishings and ornaments. Abdülmecid Efendi Library in the Mabeyn is the other principal exhibition area at Dolmabahçe.

The Mefruşat Dairesi at the palace entrance now houses the Cultural and Information Centre, which is responsible for research projects and promotion activities carried out at all the historic buildings attached to the Department of National Palaces. The centre contains a library, mainly relating to the l9th century, which is available for researchers.

The Mefruşat Dairesi at the palace entrance now houses the Cultural and Information Centre, which is responsible for research projects and promotion activities carried out at all the historic buildings attached to the Department of National Palaces. The centre contains a library, mainly relating to the l9th century, which is available for researchers.

There are cafes in the grounds near the Clock Tower, the courtyard of the Mefruşat Dairesi, the Aviary, and the Veliahd Dairesi. Items available in the souvenir shops here include books about the National Palaces, postcards, and reproductions of selected paintings from the art collection. The Ceremonial Hall and gardens are available for private receptions. Special exhibition areass have now been established, and numerous cultural and art events are held in the palace.

Mother Godess StatuetteFired clay, first half of the 6th millenium B.C., height 20 cm, Çatalhöyük. (Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

TOPKAPI PALACE MUSEUM

It is located on the promontory of the historical peninsula in İstanbul which overlooks both the Marmara Sea and the Bosphorus. The

walls enclosing the palace grounds, the main gate on the land side and the first buildings were constructed during the time of Fatih Sultan Mehmet (the Conqueror) (1451 - 81). The palace has taken its present layout with the addition of new structures in the later centuries. Topkapı Palace was the official residence of the Ottoman Sultans, starting with Fatih Sultan Mehmet until 1856, when Abdülmecid moved to the Dolmabahçe palace, functioned as the administrative center of the state. The Enderun section also gained importance as a school.

walls enclosing the palace grounds, the main gate on the land side and the first buildings were constructed during the time of Fatih Sultan Mehmet (the Conqueror) (1451 - 81). The palace has taken its present layout with the addition of new structures in the later centuries. Topkapı Palace was the official residence of the Ottoman Sultans, starting with Fatih Sultan Mehmet until 1856, when Abdülmecid moved to the Dolmabahçe palace, functioned as the administrative center of the state. The Enderun section also gained importance as a school.The main exterior gate of the Topkapı Palace is the Imperial Gate (Bab-ı Hümayun) which opens up to the Ayasofya Square. This gate leads to a garden known as the First Court. This court has the Aya Irini Church which was once used as an ammunition depot and behind the Church there

is the mint. In the past various pavillions allocated to different services of the palace were located in the First Court. In later years these have ben replaced with public buildings and schools.

Some of these are still existing. At the end of the 19th century Archeology Museum and School of Fine Arts (now Oriental Works Museum) were built in the large garden which is to the northwest of the First Court. The oldest structure in this section is the Çinili Köşk built by Fatih, which is now used as the Museum of Turkish Tiles and Ceramics. On the walls of this outer garden facing Bab-ı ali (the Imperial Gate), there is Alay Köşkü (procession Pavillion) where the Sultans used to watch the marching ceremonies. A section of the outer garden was planned by the municipality at the beginning of the 20th century and opened to the public. Known today as the Gülhane Park, the enterence has one of the larger gates of the palace. After the First Court, there is the Second Court which contains the palace buildings. It is entered through a monumental gate called Bab'us-Selam or the Middle Gate. The buildings in this court form the outer section of the palace which is called Birun. On the right there are the instantly noticed palace kitchens with their domes and chimneys and the dormitories of those who worked there. The most important of the buildings on the left side of the court are the Kubbealtı and the Inner Treasury. Behind Kubbealtı rises the Justice Tower, which is one of the symbols of the Topkapı Palace.

Some of these are still existing. At the end of the 19th century Archeology Museum and School of Fine Arts (now Oriental Works Museum) were built in the large garden which is to the northwest of the First Court. The oldest structure in this section is the Çinili Köşk built by Fatih, which is now used as the Museum of Turkish Tiles and Ceramics. On the walls of this outer garden facing Bab-ı ali (the Imperial Gate), there is Alay Köşkü (procession Pavillion) where the Sultans used to watch the marching ceremonies. A section of the outer garden was planned by the municipality at the beginning of the 20th century and opened to the public. Known today as the Gülhane Park, the enterence has one of the larger gates of the palace. After the First Court, there is the Second Court which contains the palace buildings. It is entered through a monumental gate called Bab'us-Selam or the Middle Gate. The buildings in this court form the outer section of the palace which is called Birun. On the right there are the instantly noticed palace kitchens with their domes and chimneys and the dormitories of those who worked there. The most important of the buildings on the left side of the court are the Kubbealtı and the Inner Treasury. Behind Kubbealtı rises the Justice Tower, which is one of the symbols of the Topkapı Palace.  The Harem section, which comes all the way to the back of these buildings is entered from the Third Court. Third Court is entered through the gate called Bab'üs Sa'ade (Gate of the White Eunuiches). This section of the palace is called Enderun, and it is the section where the sultans live with their extended families. Hence it is specially protected. The barracks of the Akağalar, which guard Bab'üs Sa'ade are on both sides of the gate. Tere are two structures. The first which is immediately opposite the gate is the Throne Room or the Audience Hall. Here the sultans receive the ambassadors and high ranking state officials such as Grand Visier or the Visiers. Right behind the Throne Room there is the library built by Ahmet III (1703 - 30). On the right side of the Third Court, there is the barracks of the Enderun and the Privy Treasury which is also known as the Mehmet the Conqueror Pavilion. On the side facing the Fourth Court, there is the Larder Barracks of the Enderun, the Treasury Chamber and the Chamber of the Sacred Relics. The left side starts with the Harem. The harem which covers a large part of the Palace consists of about 60 spaces of varying sizes. The main structures which are located in front of the Harem, facing the Third Court are Akağalar Mosque, Sultan Ahmet Mosque, Barracks of the Sacred Relics Guards and Chambers of the Sacred Relics. Here, the sacred relics brought back by Sultan Yavuz Selim from Egypt in 1517 are kept. The Fourth Court is entered from a covered path going from both sides of the Treasury Room. Here the buildings are located in the first part of the court, which has two sections of different levels. On the left side of this section called Lala Garden or Lale Garden there is Mabeyn which is the beginning point of Harem's access to the garden, terrace for the ladies with removable glass enclosure, Circumcission Room, Sultan İbrahim Patio and another one of the symbols of Topkapı palace, the İftariye (or Kameriye) and Baghdat Pavilion. This pavillion was built by Murad IV in 1640 to commemorate the Baghdat Campaign. At the center of the first section of the Fourth Court, there is the Big Pool and Ravan Pavillion next to it. This pavillion was also built by Murad IV in 1629, to commemorate the Revan Campaign. The side facing the second section has Sofa Pavilion (Koca Mustafa Pasha Pavilion), Başbala Tower and Hekimbaşı (Chief Physician) Room. The Sofa Mosque and Esvap Chamber and the latest built Mecidye Pavilion are on the right hand side of the Fourth Court. Out of the pavillions built on the shore of the Marmara Sea, only Sepetciler Mansion has survived until the present.

The Harem section, which comes all the way to the back of these buildings is entered from the Third Court. Third Court is entered through the gate called Bab'üs Sa'ade (Gate of the White Eunuiches). This section of the palace is called Enderun, and it is the section where the sultans live with their extended families. Hence it is specially protected. The barracks of the Akağalar, which guard Bab'üs Sa'ade are on both sides of the gate. Tere are two structures. The first which is immediately opposite the gate is the Throne Room or the Audience Hall. Here the sultans receive the ambassadors and high ranking state officials such as Grand Visier or the Visiers. Right behind the Throne Room there is the library built by Ahmet III (1703 - 30). On the right side of the Third Court, there is the barracks of the Enderun and the Privy Treasury which is also known as the Mehmet the Conqueror Pavilion. On the side facing the Fourth Court, there is the Larder Barracks of the Enderun, the Treasury Chamber and the Chamber of the Sacred Relics. The left side starts with the Harem. The harem which covers a large part of the Palace consists of about 60 spaces of varying sizes. The main structures which are located in front of the Harem, facing the Third Court are Akağalar Mosque, Sultan Ahmet Mosque, Barracks of the Sacred Relics Guards and Chambers of the Sacred Relics. Here, the sacred relics brought back by Sultan Yavuz Selim from Egypt in 1517 are kept. The Fourth Court is entered from a covered path going from both sides of the Treasury Room. Here the buildings are located in the first part of the court, which has two sections of different levels. On the left side of this section called Lala Garden or Lale Garden there is Mabeyn which is the beginning point of Harem's access to the garden, terrace for the ladies with removable glass enclosure, Circumcission Room, Sultan İbrahim Patio and another one of the symbols of Topkapı palace, the İftariye (or Kameriye) and Baghdat Pavilion. This pavillion was built by Murad IV in 1640 to commemorate the Baghdat Campaign. At the center of the first section of the Fourth Court, there is the Big Pool and Ravan Pavillion next to it. This pavillion was also built by Murad IV in 1629, to commemorate the Revan Campaign. The side facing the second section has Sofa Pavilion (Koca Mustafa Pasha Pavilion), Başbala Tower and Hekimbaşı (Chief Physician) Room. The Sofa Mosque and Esvap Chamber and the latest built Mecidye Pavilion are on the right hand side of the Fourth Court. Out of the pavillions built on the shore of the Marmara Sea, only Sepetciler Mansion has survived until the present.

During 18th. Century when the Topkapı palace took its final shape, it was sheltering a population of more than 10.000 in its outer (Birun) and inner (Enderun) and Harem sections. It shows no archirectural unity as new parts were added in every period according to the needs. However, this enables us to follow the stages Ottoman Architecture went through from the 15th to the middle of the 19th century at the Topkapı Palace. The buildings of the 15th - 17th centuries are simpler and those of the 18th - 19th centuries, particularly in terms of exterior and interior ornamentation are more complex.

Topkapı Palace was converted to a museum in 1924. Parts of the Palace such as the Harem, Baghdat Pavilion, Revan Pavilion, Sofa Pavilion, and the Audiance Chamber distinguish themselves with their architectural assets,while in other sections artifacts are displayed which reflect the palace life. The museum also has collections from various donations and a library.